The Blue Gardenia

| The Blue Gardenia | |

|---|---|

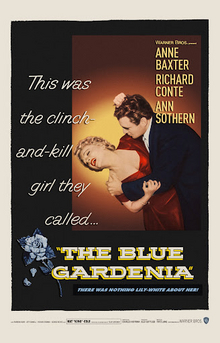

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Fritz Lang |

| Screenplay by | Charles Hoffman |

| Based on | The Gardenia 1952 novella by Vera Caspary |

| Produced by | Alex Gottlieb |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Nicholas Musuraca |

| Edited by | Edward Mann |

| Music by | Raoul Kraushaar |

Production company | Blue Gardenia Productions |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 90 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

The Blue Gardenia is a 1953 American film noir starring Anne Baxter, Richard Conte, and Ann Sothern. Directed by Fritz Lang from a screenplay by Charles Hoffman, it is based on the novella The Gardenia by Vera Caspary.[1]

An independent production distributed by Warner Bros., The Blue Gardenia – a cynical take on press coverage of a sensational murder case similar to the real-life Black Dahlia killing – was the first installment of Lang's "newspaper noir" film trio, being followed in 1956 by While the City Sleeps and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt.

The song "Blue Gardenia", performed in the film by Nat King Cole, was written by Bob Russell and Lester Lee and arranged by Nelson Riddle. The director of cinematography for The Blue Gardenia was RKO regular Nicholas Musuraca, then working at Warner.

Plot

[edit]The night of her birthday, L.A. switchboard operator Norah Larkin opens the latest letter from her fiancé, a soldier serving in the Korean War. The letter ends up revealing his plans to marry someone he met in Tokyo.

Devastated, Norah accepts a date over the telephone with Harry Prebble, a calendar girl artist. When she arrives at the Blue Gardenia, a South Seas-themed restaurant, Harry is surprised to see Norah rather than her roommate Crystal Carpeneter. He plies her with several tropical cocktails until she is soused.

Harry whisks Norah to his apartment to "show her his art". He puts on all his moves, but Norah passes out on his couch. He awakens her and attempts a date rape. She resists, striking him with a fire poker and shattering a mirror. Semi-conscious, Norah flees, leaving her suede pumps behind.

The next morning Norah is awakened by Crystal and discovers that she does not remember what happened the previous night. Meanwhile, police at a crime scene question Harry's maid. She admits to cleaning the poker and placing the shoes in the closet, ruining the crime scene.

At the telephone office, police question women who posed for Harry's drawings. When Norah learns why, she seeks the nearest newspaper account of the slaying. It revives the vague flashback of wielding the poker and shattering a mirror.

Popular columnist Casey Mayo dubs the presumed killer the "Blue Gardenia murderess" (a reference to the Black Dahlia slaying). That night, Sally Ellis, Norah's other roommate, reads aloud the newspaper report that the suspect was wearing a taffeta dress. Frightened, Norah wraps hers in a newspaper and sneaks out in the wee hours to burn it in an outdoor incinerator. She is harried by a passing patrolman for burning after hours, but let off with a warning.

To capitalize on the case's publicity, Casey writes a column calling for her to turn herself in to him rather than the police, promising fairer treatment. He receives several bogus calls from locals, but recognizes Norah's as genuine. He eventually meets her in his office. Norah tells him she is speaking for a friend, and Casey reveals that he is willing to pay for top legal representation if that friend agrees to surrender. The two later go to a diner, where Norah tells her supposed amnesiac friend's account of the murder. Casey asks to meet her friend at the diner the next day. Norah agrees, returns home and confesses to Crystal, who is sympathetic.

The next day at the diner, Crystal meets Casey and points him to Norah's booth, where she drops her gambit. He feels shocked, because he had begun to fall in love with her. He also feels guilty, admitting to her that he was only pretending sympathy for the alleged killer when he thought it was someone else. The police later arrive on a tip from the counter man and arrest Norah. Confused, she leaves convinced that Casey double-crossed her.

Leaving town, Casey notices that the music at the airport — the love theme from Tristan und Isolde — is the same composition the maid found playing on Harry's phonograph. Noticing that the records on the machine were changed, Casey realizes it is possible that Norah is innocent. Following up his hunch, Casey and Police Captain Haynes go to a music shop. The clerk says that Harry's ex-girlfriend Rose Miller sold him the record, and calls to her to come out front. Realizing the police are closing in, she locks herself in the restroom and attempts suicide.

From her hospital bed, Rose confesses. After Norah had passed out, Rose visited Harry's apartment distraught, and (implying she was pregnant) demanding that Harry marry her. He refused, and instead started playing the record that had brought them together, Tristan und Isolde. She noticed Norah's handkerchief on the floor by the record player, and enraged, a jealous Rose bludgeoned Harry with the poker.

Cleared, Norah is freed and reveals that she has forgiven Casey and wants him. After learning that she is interested, Casey tosses his "little black book" to his buddy Al.

Cast

[edit]- Anne Baxter as Norah Larkin

- Richard Conte as Casey Mayo

- Ann Sothern as Crystal Carpenter

- Raymond Burr as Harry Prebble

- Jeff Donnell as Sally Ellis

- Richard Erdman as Al

- George Reeves as Police Capt. Sam Haynes

- Ruth Storey as Rose Miller

- Ray Walker as Homer

- Nat King Cole as himself

- Dolores Fuller as woman at bar (uncredited)

- Papa John Creach as man playing violin (uncredited)

Production

[edit]The source novella for The Blue Gardenia was written by Vera Caspary and entitled The Gardenia: the eventual amendment of the film's title to The Blue Gardenia was probably intended to attract filmgoers by reminding them of the highly publicized unsolved Black Dahlia murder of 1947.[2] The Gardenia first appeared in the February–March issue of Today's Woman magazine;[3] however, the film rights for the novella had been acquired almost a full year earlier. It was announced in April 1951 that the film, then titled Gardenia, would be a production of Fidelity Pictures, whose owner, Howard Welsch, had negotiated with Dorothy McGuire to play the female lead role,[4] which was subsequently offered to Linda Darnell, Joan Fontaine,[5] and Margaret Sullavan.[6]

In September 1952, the rights to The Gardenia were sold to an independent producer, Alex Gottlieb,[3] and from then on the film was referred to as The Blue Gardenia. Despite reports that the female lead role had been assigned to Darnell,[7] and also to the little-known Vicky Lane,[8] Anne Baxter was announced for the role in November. The Blue Gardenia was considered the second of Baxter's two-picture deal with Warner Bros. as that studio signed to distribute the film. The film's two other top-billed stars were announced the same month. The film's second female lead was Ann Sothern's first cinematic role since she had been dropped by Metro Goldwyn Mayer in 1950 due to her health issues. Prior to filming The Blue Gardenia, Sothern had signed with CBS to star in the sitcom Private Secretary, filming the first episodes in the latter half of December 1952 immediately after her eight days of filming on The Blue Gardenia:[9] Sothern's focus would remain focused on television roles with occasional cinematic forays, her next cinematic credit subsequent to The Blue Gardenia being the 1964 film The Best Man. The last of the film's stars to be announced was male lead Richard Conte, who had previously starred for Alex Gottlieb Productions in The Fighter: Fritz Lang, hired by Gottlieb to direct The Blue Gardenia, had hoped to cast Dana Andrews, established as the top actor of the film noir genre, but Andrews had recently begun a sabbatical from film work.[2]

The filming of The Blue Gardenia commenced 28 November 1952 and was completed Christmas Eve, Lang wrapping the film a day earlier than its 21-day filming schedule.[3]

Reportedly Ruth Storey, the actress married to the film's leading man Richard Conte, while visiting her husband on-set during filming, accepted the producer's spontaneous suggestion that she play Rose in the film.[10] Though this role was small, it was pivotal.[11] Another key role, May, the night club's blind flower girl, – although uncredited – was played by Celia Lovsky, a long-time associate of Fritz Lang who had been instrumental in Lang's casting Peter Lorre – for a time Lovsky's husband – in M, Lang's 1931 sound film break-through.[12] Bit parts at the newspaper office were filled by the film's producer Alex Gottlieb and his wife, retired stage actress Polly Rose (sister of composer Billy Rose).[3]

Reception

[edit]When the film was first released, the staff at Variety magazine gave The Blue Gardenia a lukewarm review:

A stock story and handling keep The Blue Gardenia from being anything more than a regulation mystery melodrama, from a yarn by Vera Caspary. Formula development has an occasional bright spot, mostly because Ann Sothern breathes some life into a stock character and quips ... Baxter and Conte do what they can but fight a losing battle with the script while Burr is a rather obvious wolf. Nat 'King' Cole is spotted to sing the title tune, written by Bob Russell and Lester Lee.[13]

Film director and writer Peter Bogdanovich called The Blue Gardenia "a particularly venomous picture of American life".[3][when?] In 1965, Fritz Lang – responding to Bogdanovich's assertion - recalled the film as "my first picture after the McCarthy business and I had to shoot it in twenty days. Maybe that's what made me so venomous".[3]

In 2004 critic Dennis Schwartz gave the film a mixed review, writing:

A minor film noir from Fritz Lang (Clash by Night/The Big Heat) that never has a chance to bloom because of its dull script. It is based on the short story "Gardenia" by Vera Caspary. It plays as an unimaginative newspaper melodrama that takes jabs at the middle-class and how neurotic and fearful they are about romance. Nat 'King' Cole makes a welcome cameo as the house pianist at the nightclub called The Blue Gardenia, crooning in his velvet voice the titular theme song. Noted cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca injects the film with some intriguing noir touches, such as those ominous rain drops on Raymond Burr's window the night of the murder ... Lang himself in interviews dismissed the film as a "job-for-hire". ... But the story itself wasn't original and the acting wasn't engaging enough to elevate it past being a mild thriller.[14]

A Lux Radio Theatre adaptation of The Blue Gardenia aired on November 30, 1954, with the lead roles taken by Dana Andrews – in the role Fritz Lang had wanted him to play in the film – and Ruth Roman. Andrews later played the male lead in both the 1956 films While the City Sleeps and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt, which were the second and third installments of the "newspaper noir" trilogy that Lang began with The Blue Gardenia (Lang was not involved in the Lux Radio production).[15]

References

[edit]- ^ The Blue Gardenia at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films.

- ^ a b Hare, William (2004). LA Noir: Nine Dark Visions of the City of Angels. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. pp. 115, 120. ISBN 978-0-7864-3740-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Bergstom, Janet (1993). Copjec, Joan (ed.). Shades of Noir: A Reader. London: Verso. pp. 97–101. ISBN 978-0-86091-460-0.

- ^ Schallert, Edwin (April 26, 1951). "Old Soldiers May Link With 'Cavalry'; McGuire Deal on For 'Gardenia'". Los Angeles Times. p. II-7. ISSN 0458-3035.

- ^ Graham, Sheilah (December 17, 1951). "Hollywood Today". Arizona Daily Star. p. 11. ISSN 0888-546X.

- ^ Johnson, Erskine (May 14, 1952). "Flimsy Films Fatal to Fanfare: so say Dean & Jerry after weak plot of 'Sailor Beware'". Akron Beacon Journal. p. 12.

- ^ Stein, Herb (November 17, 1952). "Monday Morning Gossip of the Nation". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 21. ISSN 0885-6613.

- ^ Johnson, Erskine (December 9, 1952). "Deanna Durbin Not Fooling Anyone With 'Retired' Status". San Bernardino County Sun. p. 3.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (December 15, 1952). "Actress Back After Illness". Asbury Park Press. p. 10.

- ^ Parsons, Louella (December 19, 1952). "Reagan Set for TV Role with Wife". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 29. ISSN 0885-6613.

- ^ Masters, Dorothy (April 28, 1953). "Palace Back to Films with 'Blue Gardenia'". New York Daily News. p. 54. ISSN 2692-1251.

- ^ "Peter Lorre". PaidToDream.com. March 13, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ Variety. Staff film review, 1953. Accessed: August 3, 2013.

- ^ Schwartz, Dennis. Ozus' World Movie Reviews, film review, October 16, 2004. Accessed: June 25, 2013.

- ^ "The Blue Gardenia". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

Other reading

[edit]- Wager, Jans B. (21 March 2017). Jazz and Cocktails: Rethinking Race and the Sound of Film Noir. University of Texas Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-4773-1227-8.

External links

[edit]- 1953 films

- 1950s American films

- 1950s crime thriller films

- 1950s English-language films

- American black-and-white films

- American crime thriller films

- Film noir

- Films about journalists

- Films based on novellas

- Films based on works by Vera Caspary

- Films directed by Fritz Lang

- Films scored by Raoul Kraushaar

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Warner Bros. films

- English-language crime thriller films